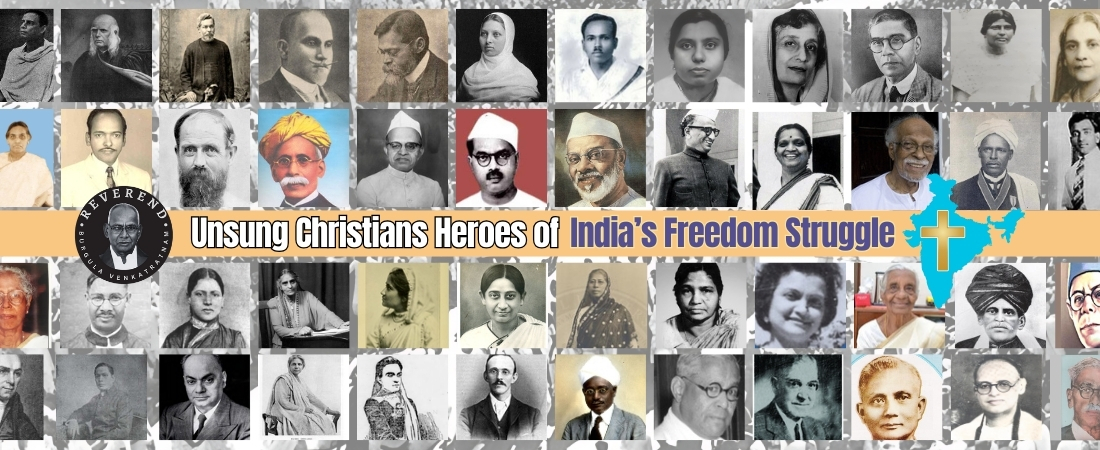

This work uncovers the overlooked contributions of Indian Christians to the nation’s freedom struggle, spanning reformers, educators, activists, and political leaders from the 18th century to 1947. Through archival research and biographical sketches, it reveals how faith, courage, and patriotism converged in the fight for independence. These unsung heroes remind us that the making of a free India was the work of many voices, united in a vision of justice and dignity for all.

Sermon Title: Faith and Freedom: The Untold Story of India’s Christian Freedom Fighters

Date: August 15, 2025.

Tagging Note: Biography & Autobiography › Historical Series.

Website: www.reverendbvr.com

Introduction: Faith and Freedom in the Indian Context

When we think of India’s freedom struggle, We remember giants like Gandhi, Nehru, Patel, Bose, Ambedkar.

But hidden in the pages of history are man unsung heroes – Christians… who fought with faith, fire, and firm resolve for India’s independence. For centuries, Christianity in India existed at the intersection of colonial politics, indigenous culture, and global missionary movements. As such, Indian Christians were uniquely placed to wrestle with questions of identity, loyalty, and justice.

The Christian involvement in India’s nationalist awakening was far from monolithic. It spanned reformist education initiatives, rural development programs, women’s empowerment movements, constitutional debates, literature, journalism, and direct political action. These contributions emerged from a theological conviction that all people are created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) and that justice and mercy are not optional virtues but divine imperatives (Micah 6:8).

Many Christian leaders had to navigate suspicion from both colonial authorities, who feared their nationalist sympathies, and from segments of the nationalist movement, which doubted their allegiance to an independent India. Yet, these individuals — some publicly recognized, others almost forgotten — demonstrated through words and deeds that patriotism and Christian discipleship could converge in the pursuit of freedom.

This work arranges sixty such figures into three broad eras. Era I (18th–Mid 19th Century) captures the intellectual and moral groundwork laid by early reformers. Era II (Late 19th Century) chronicles pioneers who blended reform with the first expressions of political self-determination. Era III (1900–1947) explores the height of Christian engagement in the mass nationalist movements that culminated in independence.

By revisiting their stories, we not only honor a neglected chapter of India’s past but also recover a vision of civic responsibility that transcends religion, rooted in the belief that truth, justice, and love are the rightful inheritance of all nations.

Era I – Early Reformers (18th – Mid 19th Century)

The first stirrings of India’s freedom movement were not forged solely on political battlegrounds but in the quieter arenas of education, social reform, and moral resistance. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, a number of Indian Christians—and sympathetic missionaries—helped prepare the intellectual soil for the nationalist awakening. Their work often challenged the colonial mindset while remaining deeply anchored in biblical principles, envisioning an India where dignity, justice, and equality were intrinsic to public life.

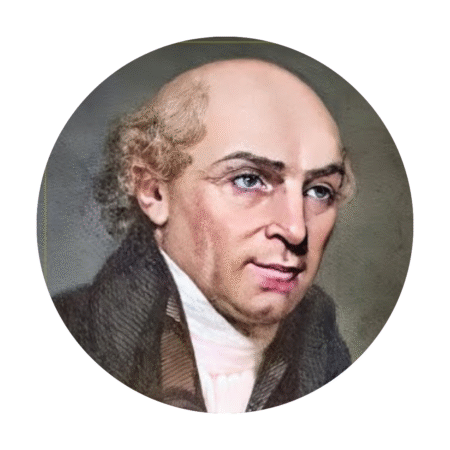

One of the earliest and most significant names is William Carey (1761–1834), an English missionary whose life’s work in Serampore transcended evangelism. He established Serampore College and was instrumental in translating the Bible into several Indian languages, but his impact extended into social reform. Carey campaigned against the sati system and infanticide, grounding his advocacy in James 1:27 — “Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress.” His vision for education—open to all castes and genders—laid a foundation for the democratization of knowledge in India.

Moving from missionary influence to the voices of Indian converts, Vidwankutty Achen (Justus Joseph) (1835–1887) emerged as a prominent Malankara Syrian Christian priest and scholar. Known for his theological depth and literary skill, he used his platform to challenge caste hierarchies within both church and society, echoing Galatians 3:28. His ministry subtly intersected with early reformist political thought by promoting the spiritual equality of all believers, a radical idea in a rigidly stratified social order.

The mid-19th century also witnessed the rise of Samuel Vedanayagam Pillai (1826–1889), widely regarded as the father of the modern Tamil novel. His Prathapa Mudaliar Charithram (1879) reflected not only literary innovation but also a vision of moral responsibility and civic virtue, values deeply informed by his Christian worldview. He believed that literature could be a vehicle for cultivating national consciousness, preparing the ground for political activism.

In Bengal, Rev. Lal Behari Dey (1824–1894) exemplified how Christian intellectuals engaged with Indian traditions. A convert from Hinduism and a Cambridge-educated scholar, Dey preserved and published Bengali folktales while simultaneously promoting education and social upliftment. His work bridged indigenous culture with Christian ethics, resisting the colonial narrative that equated Westernization with progress.

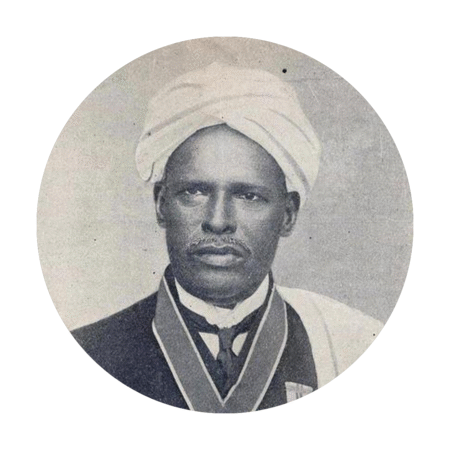

Parallel to these reformers stood Rao Sahib Abraham Pandithar (1859–1919)—though chronologically straddling the cusp of Eras I and II—whose ethnomusicological work preserved South Indian musical traditions against the tide of cultural erasure. His efforts embodied Psalm 150’s celebration of music as a divine gift and served as an assertion of India’s rich cultural sovereignty.

The reformist impulse in this period was not only intellectual but also medical and humanitarian. Dr. Fanny Jane Butler (1850–1889), one of the earliest British women doctors in India, dedicated her career to providing medical care to women in Kashmir who were denied treatment by male physicians. In her, one sees the embodiment of Matthew 25:36—“I was sick and you looked after me.” Although a foreigner, her work directly countered systems of neglect that colonial administration had failed to address.

Collectively, these early reformers forged the ideological scaffolding upon which later nationalist activism would be built. By promoting literacy, cultural preservation, gender justice, and public health, they quietly undermined colonial paternalism. Their faith-infused vision of service and human dignity would ripple forward into the next generation of leaders, setting the stage for the more overtly political Christian pioneers of the late 19th century.

Era II – Late 19th Century Pioneers (1850–1899)

The closing decades of the 19th century marked a decisive shift in India’s journey toward independence. The reformist groundwork laid earlier began to intersect with an emerging sense of political agency. For Indian Christians, this era saw a deepening involvement in organized reform movements, journalism, and the earliest articulations of self-rule, often framed through biblical ethics and the conviction that all humans are created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27).

In Bengal, Kali Charan Banerjee (1847–1907) stood as a lawyer, legislator, and Christian apologist who refused to see his faith as incompatible with nationalism. As a member of the Bengal Legislative Council, he advocated for Indian representation in governance, drawing upon the principle of justice central to Micah 6:8 — “To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God.” His speeches fused constitutional reform with moral responsibility, inspiring many young Indian Christians to view political engagement as a form of service to God.

Another towering figure of this era was Krishna Mohan Banerjee (1813–1885), an early convert from Hinduism and a pioneering Christian intellectual. Though his life spanned both Eras I and II, his later years were marked by a public defense of Indian rights within the colonial system. As an educator and writer, he championed the view that Christian faith should strengthen, not sever, one’s national identity. His involvement in educational reform reinforced the belief that enlightenment through learning was a pathway to liberation.

The spirit of fearless contextualization of faith was epitomized by Brahmabandhab Upadhyay (1861–1907). Born Bhavani Charan Banerjee, he embraced Catholic Christianity while remaining deeply rooted in Hindu philosophical traditions, calling Christ “the fulfillment of the Vedas.” A bold advocate of Swaraj, he linked India’s political freedom with spiritual awakening, echoing John 8:32 — “Then you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

Education as a means of empowerment found a champion in S. K. Rudra (Susil Kumar Rudra) (1861–1925), the first Indian principal of St. Stephen’s College, Delhi. Under his leadership, the college became a hub for nationalist dialogue, with students often drawn into discussions on self-determination. Rudra maintained that intellectual formation was inseparable from moral formation, a conviction that resonated with Proverbs 4:7.

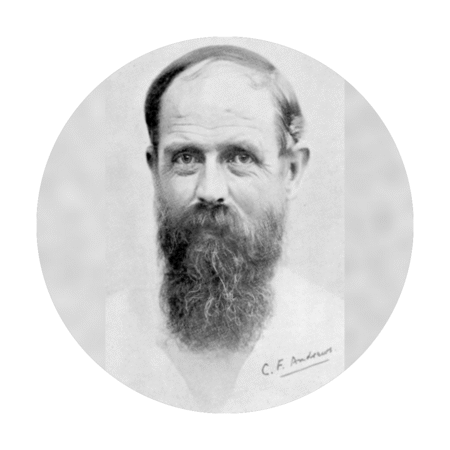

While Indian Christians were stepping into leadership, allies from abroad also left an indelible mark. C. F. Andrews (1871–1940), nicknamed Deenabandhu (“Friend of the Poor”) by Gandhi himself, was an Anglican missionary who became one of the most trusted mediators between British authorities and Indian nationalists. Andrews’ advocacy for indigo workers and indentured laborers was driven by Isaiah 58:6 — “Is not this the kind of fasting I have chosen: to loose the chains of injustice… and set the oppressed free?”

The closing years of the century also saw the emergence of women leaders whose social service and advocacy challenged both patriarchal norms and colonial injustices. Pandita Ramabai (1858–1922), though continuing her work into the next century, began her public career in the late 1800s as an educator and champion for widows. A convert to Christianity, she founded the Mukti Mission, blending faith with a fierce defense of women’s dignity, reflecting Proverbs 31:8–9.

In parallel, Cornelia Sorabji—India’s first woman to study law at Oxford—began her legal activism in the 1890s, advocating for the rights of purdahnashin women. Her work, steeped in the ethic of Proverbs 31:9, prefigured the legal reforms that would come with independence.

By the turn of the century, these pioneers had helped embed a vision of national service in the Christian conscience. Their combined efforts—whether in the courtroom, classroom, press, or pulpit—had moved Indian Christianity from a quiet reformist current to an active, if still often underestimated, force in the broader nationalist tide. They had demonstrated that Christian ethics could stand not in opposition to Indian nationalism but as one of its moral engines.

Era III – 20th Century Leaders (1900–1947)

The dawn of the 20th century brought a new urgency to India’s freedom struggle. The nationalist cause, once the pursuit of reformist intellectuals, transformed into a mass movement engaging workers, farmers, women, and students. For Indian Christians, this was both a challenge and an opportunity: a challenge to prove their loyalty to India in the face of suspicions about colonial associations, and an opportunity to show that the Gospel’s call to justice, mercy, and peace could align with the cry for Swaraj.

Among the early leaders of this period was J. C. Kumarappa (Joseph Chelladurai Cornelius Kumarappa), an economist and Gandhian who became a key architect of India’s rural economic policy. Rejecting purely industrial models, Kumarappa advanced a “Gandhian economics” rooted in self-sufficiency, stewardship of resources, and equitable distribution — values that resonated deeply with Acts 4:34–35. His vision placed the village at the heart of national regeneration.

On the frontline of non-violent activism was Titusji, a devout Christian who joined Gandhi’s Salt March in 1930. Marching alongside Hindus and Muslims, he embodied the truth of Psalm 133:1 — “How good and pleasant it is when God’s people live together in unity!” His presence challenged stereotypes about Christian disengagement from nationalist struggles.

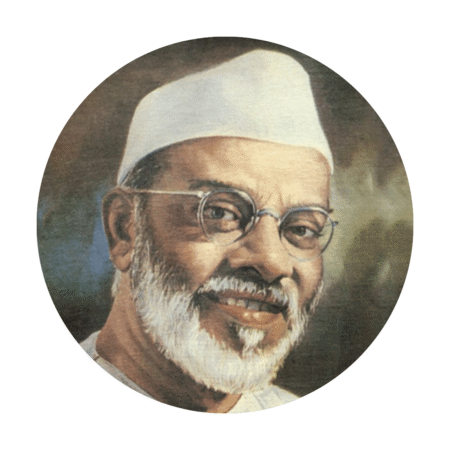

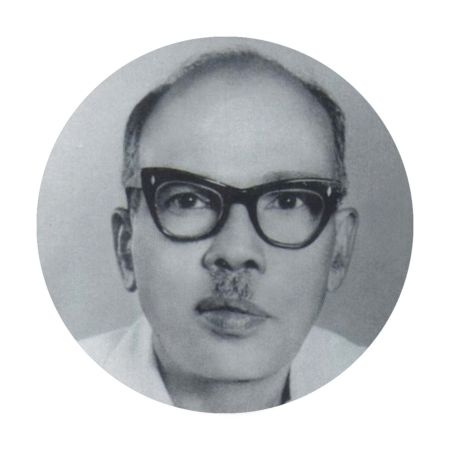

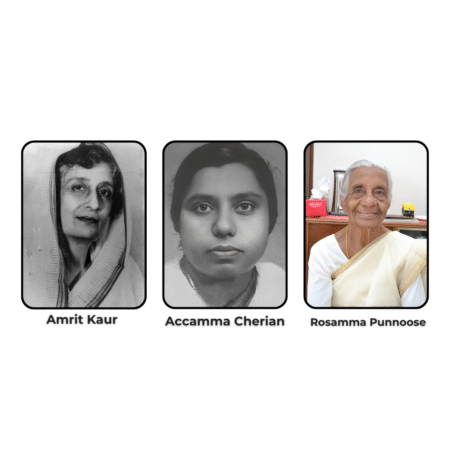

Women played a transformative role in this era. Amrit Kaur (Rajkumari Dame Bibiji Amrit Kaur), the first Health Minister of independent India, was a tireless advocate for public health, women’s education, and the abolition of child marriage. Her Christian convictions undergirded her campaigns for human dignity, aligning with 1 Corinthians 6:19–20. Similarly, Accamma Cherian, hailed as the “Jhansi Rani of Travancore,” led large-scale protests against the princely state’s repressive policies, facing imprisonment with the courage of Esther 4:14. Rosamma Punnoose, an activist and later legislator, wove together her faith and her commitment to workers’ rights.

Legal and political leadership also featured prominently. Cornelia Sorabji, whose early career began in Era II, continued into the 20th century, expanding her advocacy for women in seclusion. Joseph Baptista, a Roman Catholic barrister and political leader, coined the slogan “Swaraj is my birthright and I shall have it,” later popularized by Tilak. He bridged communities, defending the rights of political prisoners and promoting inclusive nationalism.

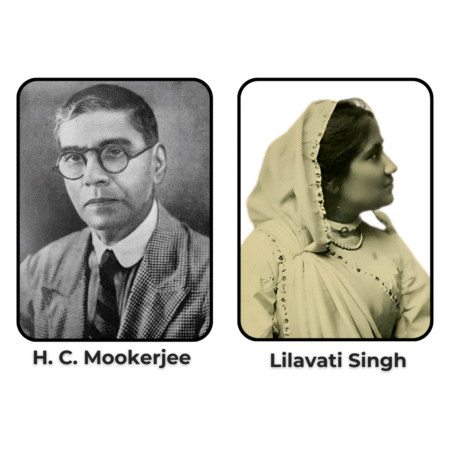

Christian statesmen such as Harendra Coomar Mookerjee, later Governor of West Bengal, played a crucial role in the Constituent Assembly, ensuring constitutional safeguards for minorities while supporting the national vision. Lilavati Singh, educator and women’s rights advocate, advanced female literacy and leadership within both church and society.

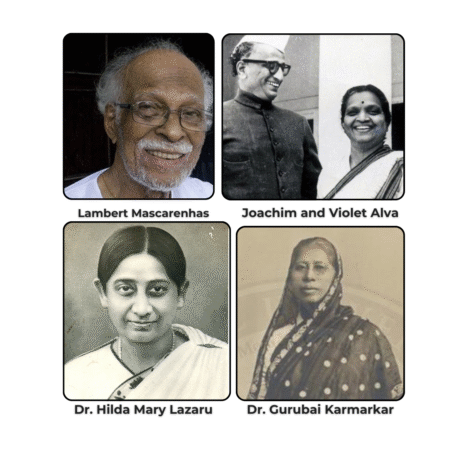

Other notable leaders from this period include Lambert Mascarenhas, a journalist whose writings in Goa Today and nationalist papers exposed colonial exploitation in Portuguese territories; Joachim and Violet Alva, a political couple who served in the legislature and promoted social justice; Dr. Hilda Mary Lazarus, a pioneering Christian woman in medicine who headed major hospitals; Dr. Gurubai Karmarkar, a medical missionary serving rural communities; and Annie Mascarene, one of the first women to be elected to the Constituent Assembly.

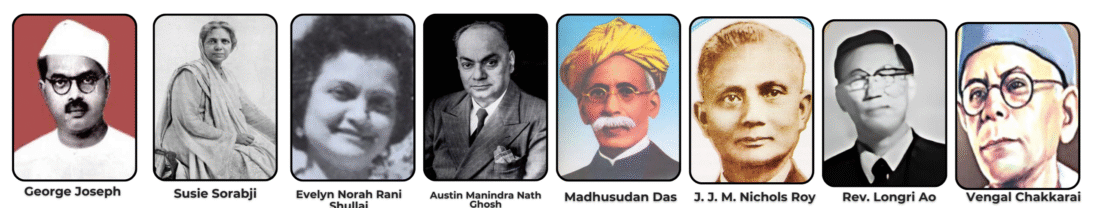

Regional diversity was a hallmark of Christian nationalist engagement. George Joseph, a Kerala-born lawyer in Madurai, defended political activists in court; Susie Sorabji championed education for girls; Evelyn Norah “Rani” Shullai from the Khasi Hills advanced women’s leadership in education; Austin Manindra Nath Ghosh contributed to student movements; and Madhusudan Das of Odisha used his legislative influence to protect linguistic and cultural identity.

In the northeast, J. J. M. Nichols Roy was instrumental in securing constitutional provisions for tribal self-governance, while Rev. Longri Ao worked to reconcile communities during political transition. In the south, Vengal Chakkarai served as both a civic leader and theologian, integrating Indian thought into Christian theology. Constance Prem Nath Dass advocated for women’s education, Alice Maude Sorabji Pennell brought medical care to underserved communities, and K. T. Paul championed cooperative movements for rural upliftment.

The armed services were represented by figures like Major General A. A. Rudra, who broke racial barriers in the Indian Army, paving the way for post-independence Indian military leadership. Paul Ramasamy organized labor movements, linking nationalist aspirations to workers’ rights. Gracy Aaron worked to empower Christian women in civic life.

William Howard Campbell engaged in agricultural development for rural self-reliance, John Matthai served with distinction in the Constituent Assembly and later as Finance Minister, and A. J. John, Anaparambil held leadership roles in both politics and education. Prof. C. P. Mathew fostered political awareness through his academic work.

Intellectual contributions came from Krupabai Satthianadhan, whose literary works inspired reform; Samuel Higginbottom, whose agricultural institute transformed rural economies; Margaret Pavamani, who empowered destitute women; Gurram Jashuva, whose poetry gave voice to Dalit aspirations; Dr. Lucy Oommen, who served tirelessly in rural health; Bishop V. S. Azariah, who championed an indigenous Indian church; Sarah Chakko, the first woman president of the World Council of Churches; Joseph Macwan, who addressed social injustice through literature; and Dr. G. D. Boaz, who established psychology as an academic discipline in India.

Others, like Rao Sahib Abraham Pandithar, preserved cultural heritage; Dr. Gift Siromoney, a post-independence scholar, continued the ethos of cultural revival; Dr. Fanny Jane Butler, John Aloysius Thivy, Dr. Isaac Santra, Rev. Sudhir Kumar Chatterjee, and Raja Sir Harnam Singh each bridged the worlds of service, culture, and politics in unique ways.

By 1947, these leaders — diverse in region, gender, profession, and denominational background — had demonstrated that Christian faith was not an obstacle to patriotism but a source of courage, sacrifice, and vision. Their lives echoed the words of Jesus in Matthew 5:14 — “You are the light of the world. A city set on a hill cannot be hidden.” Together, they illuminated a path where spiritual conviction and national liberation walked hand in hand.

Conclusion

The freedom struggle was never merely a political project; it was, at its heart, a moral awakening. Indian Christian leaders, whether in the pulpit, classroom, field, courtroom, or protest march, brought to this awakening a distinctive blend of faith and action. For them, the biblical call to “seek the peace and prosperity of the city” (Jeremiah 29:7) applied as fully to colonial India as it did to the ancient exiles of Scripture.

From William Carey’s early campaigns against sati to J. C. Kumarappa’s Gandhian economics; from Pandita Ramabai’s defense of women’s dignity to Joseph Baptista’s rallying cry for Swaraj; from Bishop V. S. Azariah’s vision of an indigenous church to Accamma Cherian’s fearless leadership in street protests — these figures show the breadth of Christian engagement with the Indian nationalist cause.

Their contributions defy simple categorization. Some worked within the structures of colonial governance to push for reform; others stood outside, aligning with mass movements for civil disobedience. Some wielded the pen, others the plough, others still the tools of medical or legal professions. Yet all shared a common moral compass, one shaped by the life and teachings of Jesus Christ.

In the decades since independence, the public memory of Christian freedom fighters has often faded, overshadowed by dominant political narratives. Restoring them to the historical record does more than fill a gap; it challenges us to recognize that the making of a free nation requires many hands and many voices, some of them willing to risk being forgotten in order for justice to prevail.

Their legacy endures not only in the annals of history but in the continued struggles for justice, equality, and dignity in India today. As the Apostle Paul wrote in Galatians 5:13 — “You, my brothers and sisters, were called to be free. But do not use your freedom to indulge the flesh; rather, serve one another humbly in love.” This service — humble, courageous, and sustained — is the lasting inheritance of India’s Christian freedom fighters.

This list is by no means complete. It will be updated to include many more men and women whose lives and work contributed to the making of the Indian nation.

© 2025 ReverendBVR.com | High-Academic Sermon Series, 2025.

Content licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). You are free to share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format with proper attribution. No commercial use or modifications allowed without explicit permission.

For further sermons and biblical reflections, please visit 🌐 www.reverendbvr.com/sermons